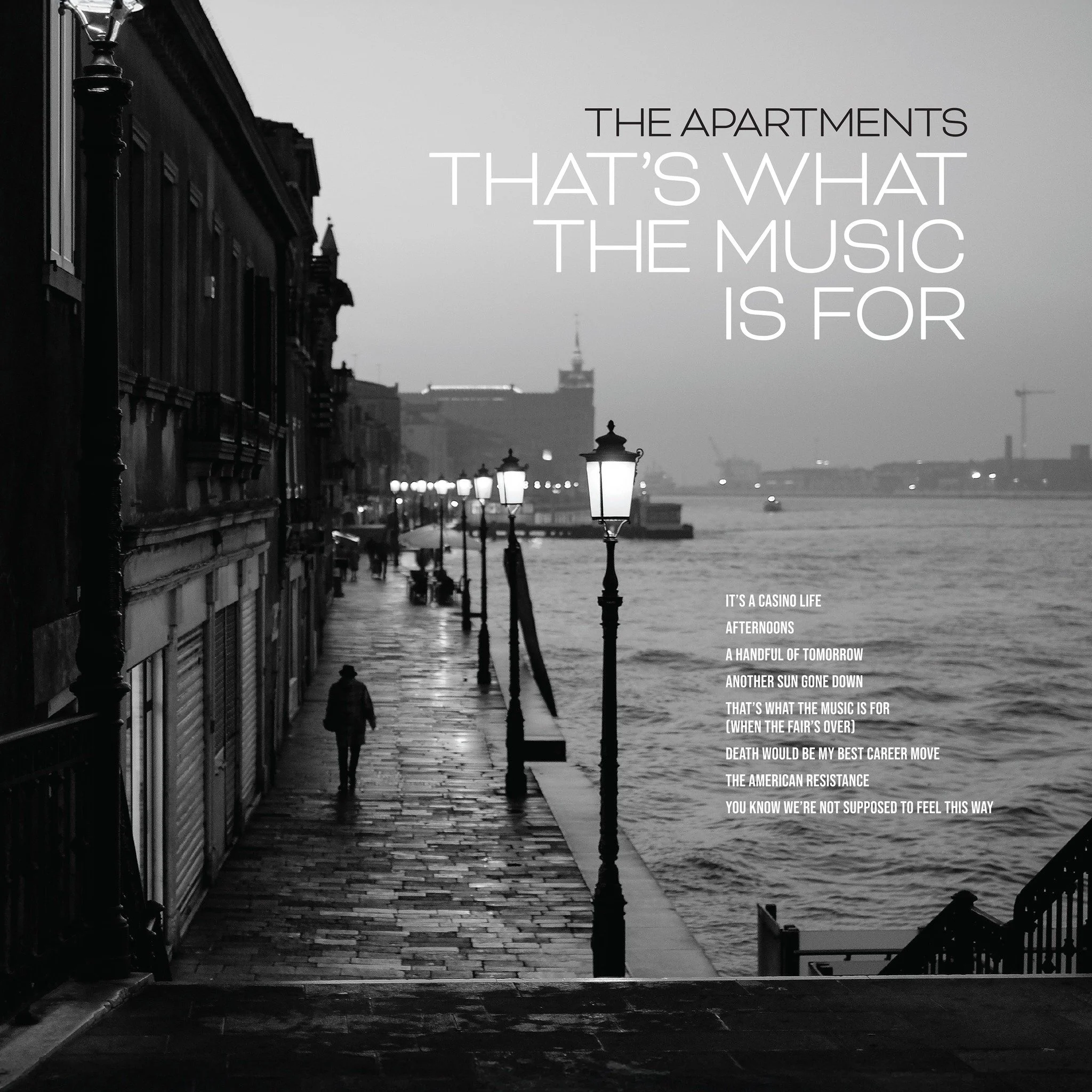

that’s what the music is for

new album - 17 oct 2025

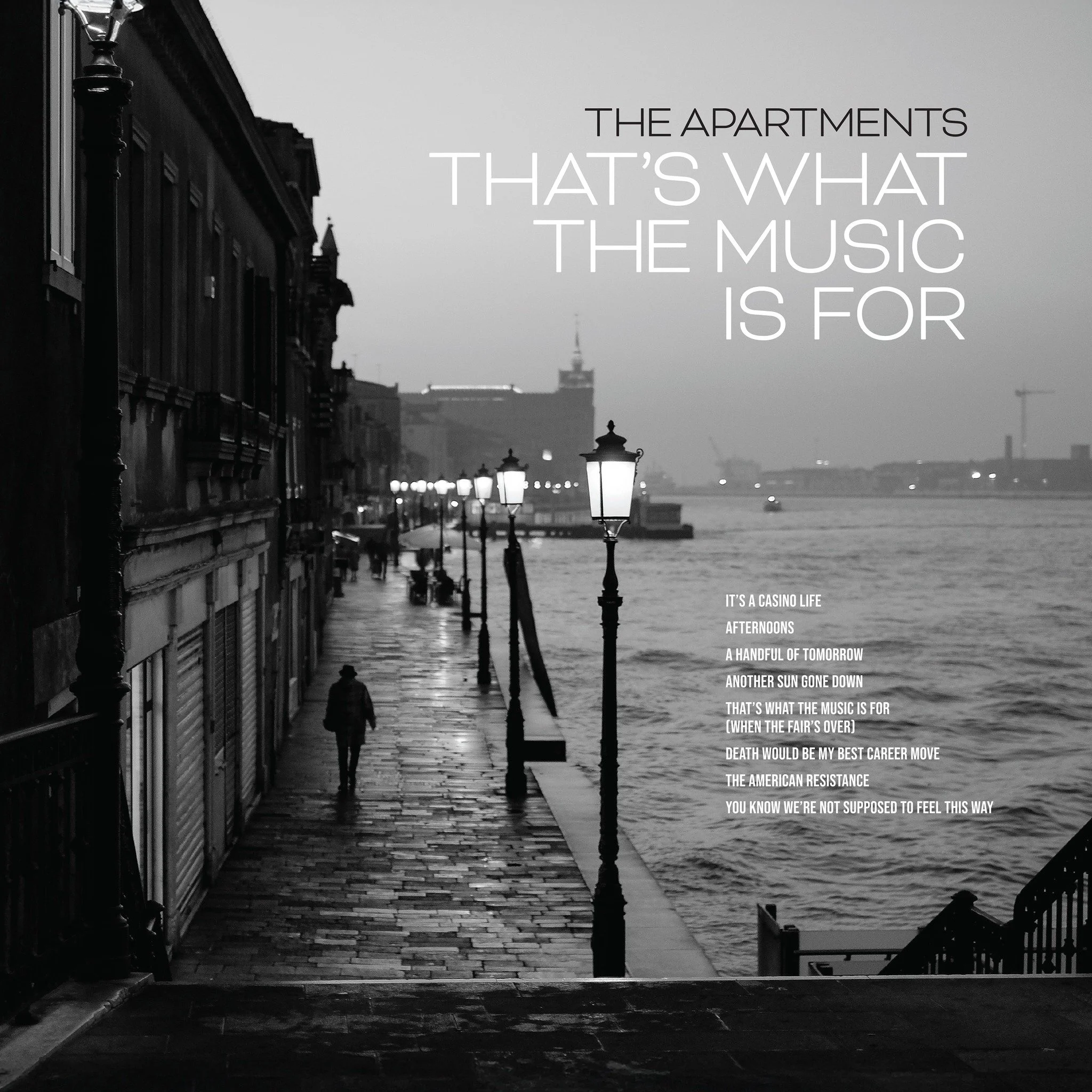

The Apartments tenth album That’s What the Music is For is a cycle of eight songs that speak to one another to tell the album’s story. Available now and supported by The Apartments on Tour.

Reviews to date

That’s What the Music is For was listed as #1 on Bandcamp’s Essential Releases. “It’s the kind of record that demands you stop what you’re doing and pay attention, then rewards your focus with careful, patient storytelling and heartbreaking melodies” USA

“An album about existing in a space where nothing is as straightforward as joy or sadness…It’s another beautiful record. One that pulls at the threads of memory and holds you in a very alive present that’s complicated but still graspable. Bernard Zuel, AU

“8/10…emphasises his proudly perfectionist nature, it’s exquisitely understated… drenched in resonant yearning” Wyndham Wallace UNCUT, UK

“… mood music for moody people… songs for those nights when you know you’re going to have the mother of all hangovers in the morning.” Louder Than War, UK

“Glorious music for bright, wintry days…these are songs to get lost in, at times seriously dramatic…subtle and lovely. And it’s not just how the music sounds, but how it makes you feel. It’s an album that changes the atmosphere in the room, possibly The Apartments’ finest album to date.” No More Workhorse, IE

“Each album by The Apartments recounts the seasons…with a certain je ne sais quoi reminiscent of prints, sepia tones and watercolors…sketches and details that weave a path back to the past. Peter Milton Walsh composes like a painter, mixing colors and nuances. These eight songs have the flavour of twilight.” Benzine Magazine, FR

“A wonderful album... that will warm the autumn and winter evenings with …melancholy.” De Krenten Uit De Pop, NL

“Lives up perfectly to its title … invites us to dive deep within ourselves … what keeps us alive.” Sun Burns Out, FR

“What we consider once or twice in a lifetime events become the bread and butter of the Apartments’ musical soul, and that’s fine with us. “Bring back the days that had you in them,” Walsh croons guilelessly in the title track…Nostalgia, yearning, understanding, catharsis, all in two clean and elegant lines. Nobody ponders loss like Peter Milton Walsh, and thank the gods for that.” The Big Takeover USA

”Yet another great album from The Apartments, of melancholic and autumnal songs that tell of that which is forever gone, that which is destined to end and of the place of music in our lives. Peter Milton Walsh is one of the greatest songwriters around, and The Apartments music survives on the unconditional love of all who listen to it.” LOUDD, Italy

Available online and in select record stores in limited white vinyl, black vinyl, CD, and digital.

use the links below to buy online in australia THROUGH MGM and globally THROUGH TALITRES IN FRANCE

Two singles have been released - “A Handful of Tomorrow” and “Death Would Be My Best Career Move” -

and are accompanied with videos directed by Nick Langley - see links below

2025 album lauch tour australia

melbourne sat 15th november: George Lane st kilda

Sydney 17th October - LOW302 Surry hills

brisbane 25th october - the junk bar new farm

In mid-2026 the apartments are planning to tour Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth

tournée française 2026

angers - 25 mars - le chabada

rouen - 26 mars - le 106

METZ - 27 Mars - Les Trinitaires

tourcoing - 29 mars - le grand mix

Paris - 31 mars - le petit bain

Saint nazaire - 1 Avril - Le VIP

ANGOULÊME - 2 avril - la nef

bordeaux - 3 avril - le rocher de palmer

volvic - 4 avril - les vinzelles

plus de détails à venir

Where to buy the apartments music?

To buy the apartments on CD or Vinyl use these links for mail order in Australia VIA MGM and worldwide VIA TALITRES FRANCE

Où acheter la musique de The Apartments

Pour acheter The apartments sur CD ou Vinyle utilisez ces liens pour TALITRES FRANCE

The Apartments catalogue

NEW ALBUM OCTOBER 2025: Thats What the Music is For - CD + Vinyl

In and Out of the Light - CD + Vinyl

No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal - CD (Australian CD with 2 bonus tracks) + Limited Vinyl (NOW via Talitres)

Live at L’Ubu - vinyl

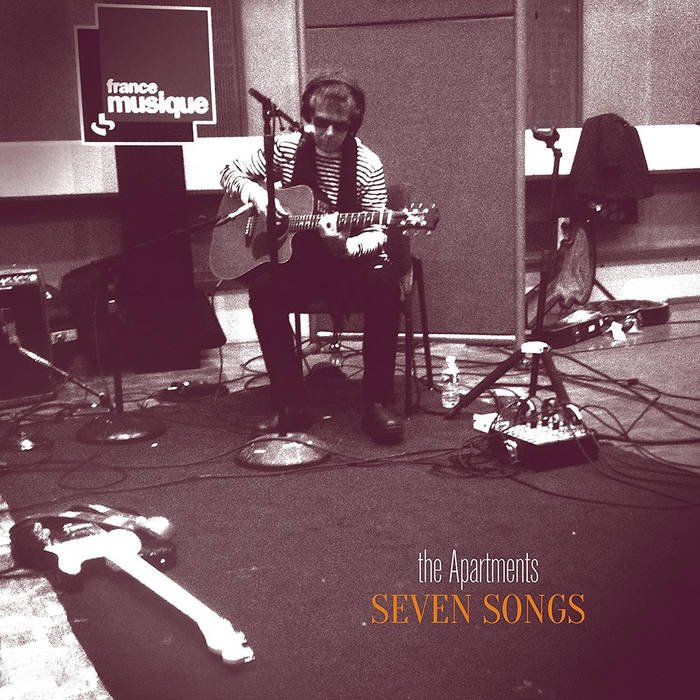

Seven Songs - CD + Limited vinyl

A Life Full of Farewells - CD + Limited vinyl

apart - Limited vinyl

fête foraine - CD + Limited vinyl

drift - CD + Limited vinyl

the evening visits … and stays for years - CD + vinyl - limited re-issue

The Apartments on bandcamp

re-issues

apart - on vinyl for the first time

The Apartments album, apart, is now available for the first time with limited edition Arctic White plus Classic Black vinyl available.

Lovingly mastered by Don Bartley for double LP, apart has never sounded better. First released on CD in 1997 with a limited run of 3,000 apart quickly sold out in Australia and Europe. Apartments fans finally have the chance to get this vital missing piece of the discography on vinyl and digital.

apart contains some of the most exquisite and timeless pieces from the songbook of The Apartments’ Peter Milton Walsh. Piano, trumpet, strings, and beats step forward on apart in songs brought together by players such as Chris Abrahams of The Necks on piano, Ken Gormley of The Cruel Sea on bass and Gene Maynard on drums.

Sprinkled throughout are instrumental haikus and subtle jazz inflections. Dave Graney, in Welcome to Walsh World, sets a dark, captivating rendition of Baudelaire’s To the Reader against a seductive background of piano, bass and drums.

Recorded at Electric Avenue Studio in Sydney in 1997 with Chris Abrahams (The Necks), Ken Gormley (The Cruel Sea) and Dave Graney, apart is a summery yet nocturnal record that speaks of passing time, the present moment and an already dawning future.

Original artwork has been updated for this long awaited vinyl release by Pascal Blua, the French graphic artist behind the artwork for No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal.

The release includes a set of 6,000 word liner notes written by Peter Milton Walsh that provide a revealing insight into the albums genesis, recording and release. Due to personal events, a long period of silence from The Apartments followed apart, until 2015’s acclaimed No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal, the album that bookends this vinyl release.

REVIEWS

Is it possible for an album to be tender and joyful while never shaking loose a patina of unspoken, and maybe unexplainable, sorrow. Sorrow that is a little beyond melancholy without ever really nudging despair.

In a similar way to Nick Cave’s Skeleton Tree, the songs on this album seem to portend the future and will be heard forever in that context. They carry an ache of indeterminate shape while leaving space for your own ache—which is really quite special.

Walsh’s beautifully written essay constitutes 6,000 words of rewarding insight. Bernard Zuel, Music Journalist

A lush, moving piece of work…if there’s a parallel to be made here, apart can be seen as an Antipodean equivalent to Berlin, Lou Reed’s bleak masterpiece of domestic melodrama. Andrew Stafford, The Guardian

vinyl aVAILABLE AT …

- Outside of Australia: apart is available in globally at select record stores and via Talitres Bandcamp

- Australia: apart will be available at select records stores after 1 March 2024 and online through MGM Distribution

seven songs - second Release on vinyl

In December 2012, The Apartments, led by Peter Milton Walsh, toured France, playing a series of mythical shows in venues across France, along with some acoustic sideshows in Art Galleries & music stores.

For this tour, The Apartments had a seven-piece band—guitars, bass, drums, violin, tambourines and percussion, singers, piano, organ and trumpet. Amanda Brown formerly of The Go-Betweens was on violin and vocals and Nick Allum formerly of Fatima Mansions who had played in the finest English incarnation of The Apartments was on drums. Wayne Connolly from Australian band, Knievel, who ended up producing The Apartments’ acclaimed 2015 comeback album No Song No Spell No Madrigal, played guitar.’

Early on in the tour, the band dropped into the studios of France Musique to record a beautiful live session for Vincent Théval’s Label Pop program, a French public radio show that is broadcast and streamed at 10.30 each Monday night to an international audience.

As Peter Milton Walsh wrote on the back cover… “Saturday afternoon in Paris—a recording session with the band, a French radio studio built in the Sixties…it feels like some kind of destiny is at play. Songs will be revised and relived in this room. Songs from long ago seem set once more in the present. Years condense into a set. Seven players. Seven songs. Someone picks up a tambourine. Bang! And we begin …”

This live recording, Seven Songs includes some of The Apartments’ greatest selection from the band’s songbook that were met with strong responses from fans and critics during the 2012 tour.

Seven Songs was originally released on vinyl for 2013 Disquaire Day, France’s version of Record Store Day as a limited edition run of 500.

In 2022 French label Talitres released a run of 500 CDs. Both issues quickly sold out globally.

Seven Songs has now been re-released by Talitres in 2023 in a limited edition run of 500 pressings.

The European allocation of vinyl is selling fast, and the Australian allocation is now available from 1 March 2024 for the first time in Australia through MGM.

Available on vinyl at select record stores or mail order via our links

Available on all digital platforms

apartments t-shirts and tote bags

T-SHIRTS (WOMEN/MEN) AND TOTE BAGS now available through Big Cartel.

Women: Fitted Tee, 100% Soft Cotton. SMALL, MEDIUM and LARGE

Three colours: Classic Black, Cherry Red and Sports Grey

$40.00 AUD plus postage

Men: Classic Fit Tee, Heavy Cotton.

SMALL, MEDIUM, LARGE

Three colours: Black, White and Sports Grey

Note: Currently NO Medium and Large Black Men’s Tees available ONLY WWHITE & SPORTS GREY

$40.00 AUD plus postage

EXTRA-LARGE = Red, Black, Dark Grey, Light Grey and White available

2XL & 3XL

Available in BLACK only

$30.00 AUD plus postage

AND The Apartments Tote Bags

$30.00 AUD plus postage

THE SHOP IS NOW OPEN

Women’s Tees

Men’s Tees

Tote Bag

The Apartments live videos

The Apartments line-up includes the European band, sometimes a trio, sometimes a full band, the Australian band and The Apartments as a duet. We are aiming to have some live videos from each of these regions with all line ups. There is a lot going on here!

The Apartments

September 2015 / Live at L’Ubu, Rennes, France

Watch more videos

the apartments FACEBOOK

FOLLOW THE APARTMENTS ON FACEBOOK

initialspmw Instagram

Follow Peter Milton Walsh of The Apartments on Instagram

Podcasts

Over 2020 and 2021 Peter Milton Walsh spoke on a number of podcasts from around the world. Here’s a selection to start with. Click on the boxes for a link to the podcast.

words

TLDR version: Read ‘My Rock’n’Roll Friend’ by Tracey Thorn.

Photo Kate Wilson

You think you know somebody, then you read a bio and realise how little you know them after all.

I got that feeling in spades from Tracey Thorn’s ‘My Rock’n’Roll Friend’. It’s about Lindy Morrison, about the friendship that developed between Tracey and her and about their solidarity not just as women, but as women in music. The great Elizabeth Hardwick, asked once whether writing was the same for men and women, said “Nothing is the same for men and women.” Ditto music.

So it’s both a personal and social history, a racing read knocked over in a couple of hours yet so richly written that both the small and larger truths resonate long after.

The book opens with a double-edged epigraph from Margaret Atwood, as if warning the reader—and maybe the subject too—what’s coming. “She will have her own version. But I could give her something you can never have, except from another person: what you look like from outside…This is part of herself I could give back to her.”

Tracey thought the world should know the story of her wonderful pal and set out to honour her in writing. I figured I’d be reading a portrait of a lady on fire, and I am so here for that.

Yet in writing about a friend, friendships can, ironically, be put at risk. How willing are any of us, after all, to have our story told through someone else’s eyes?

If she were as honest about me as she is about herself in her memoirs, I’m not sure I’d like to be on the receiving end of Tracey’s unsparing gaze. That said, now that I know how intriguing Lindy’s backstory is, and how they seesawed and shifted in one another’s lives, I understand why she felt compelled to write this story, their story. Why, I might even have been tempted to write it myself, were it not for the fact that I’m not a writer and I don’t have a death wish.

A river of surprises runs through this book. The first and largest for me was in the person that Lindy used to be.

The Lindy Morrison I met in 1978 seemed bulletproof, so outrageously self-confident you could not imagine she’d had a moment of insecurity in her entire life. She brought her own electricity to every room.

I saw the same unchanging person in a hundred different situations from that time onward. No mute button, or sense of anything withheld, a permanent refusal to tone down. She would have to ask Siri what “undershare” means.

And that’s the Lindy who burst into Tracey’s life too in 1983—and became her heroine.

Yet through diary entries and letters to herself as a teenager, Lindy reveals a poignant vulnerability that came as a shock. Pages from those years reveal her wishing she was more pretty, worrying her Coke-bottle glasses will put boys off, wondering if she would ever find love, all of this escalating a teenage sense of loneliness. She was so hard on herself.

What is it that makes us who we are? How much of the past carries into the present? It’s as if the trauma cleaners had been through and removed the clues and evidence of who Lindy had once been in a way that makes Gatsby’s strenuous remaking of himself look positively indolent.

Tracey tries to work out how she became the Lindy 2.0 we all came to know.

And while there are many other fantastic revelations, some apparently were cut because they fitted a category I had no idea even existed: “Too revealing for Lindy Morrison.”

Some of these scenes seem to say “Alright Mr DeMille, I'm ready for my Netflix series now”. Diaries summon up a lost way of life, such as the way in which Lindy’s generation travelled. You see her with her friend Diana, blonde hippie chicks hitchhiking through a “Europe on $5 a Day” world of 1-star hotels, traveller’s cheques and trips you’d take only if you were heroically out of it, such as heading for Algiers from Fez when they’re both struck down with dysentery—which I think rather gallant.

And all of this is set during the age of letters, which was the way most travellers kept in touch. Getting news from home through the mail, picked up every couple of weeks from Poste Restante. No mobiles, FB/Instagram, email.

The big danger in writing about events of 30 or 40 years ago is that it might lapse into recollections in tranquillity. Not here. This story has the immediacy and emotion of the time itself, with the storms both Tracey and Lindy lived through, how they felt back then perfectly preserved in vivid letters and diary entries they kept at the time. Hindsight could not hope to be this honest.

There is no glossing over the volatility of their friendship because friendships—like careers, marriages and socials—take an awful lot of work. They are not long, the days of wine and roses. Everything changes. And you sense the great shifts as the friendship is tested by the usual suspects of distractions, distance and different timezones.

There are tensions and silences and misunderstandings all of which the years can magnify yet which can just as easily fly out the window, given the right time and place. Once friends, alcohol and reminiscence are together in the same room, any letdowns vanish in wild laughter.

The writing moves like music, changing key just as life does and just as swiftly, from the heartbreaking to the hilarious, gradually gathering up the full sound of Lindy in all her complicated contradictory glory. She shines brightly.

But while truth will not always favour the teller, Spoiler Alert: their friendship, like a song, reveals and proves itself over time. It lasts.

Peter Milton Walsh 29 July 2021

Un Samedi Après-Midi à Paris

(Traduction française de Jean-Baptiste Santoni avec l'aide précieuse de Catherine Cernicchiaro)

Décembre 2012. Premiers jours de l’hiver. Nous entrons dans Paris un samedi après-midi, pour une session qui sera enregistrée dans le cadre de l’émission Label Pop de Vincent Théval. C’est une émission écoutée par un public fervent, diffusée partout en France tous les lundis à 22h30 sur une station de radio publique française, et accessible en ligne partout dans le monde. Nous arrivons d’Allonnes, près du Mans, où nous avons joué la veille au soir le premier concert de la tournée The Apartments.

Je suis assis à l’arrière du van avec Amanda, Wayne et Nick. C’est Robin Dallier, notre fabuleux technicien son pour cette tournée, qui conduit. J’ai appris seulement la veille qu’alors tout jeune ingénieur du son, Robin avait été assistant lors de l’enregistrement de Amours des feintes de Jane Birkin le dernier album et la dernière chanson jamais écrits par Gainsbourg. Six mois plus tard, Serge mourait.

Souvent, tôt dans la journée, Serge et Robin se retrouvaient seuls dans le calme du studio. Ils fumaient et discutaient en buvant du café, et Serge terminait d’écrire des paroles avant que Jane ne vienne pour les chanter. Je me dis que ce n’était que le début pour Robin. Pour Serge, c’était déjà presque la fin.

Le charme est soudain rompu lorsque nous prenons un tournant brusque qui fait pencher le véhicule. Celui-ci semble ensuite bondir hors du Périphérique, et nous voilà au milieu de cet inoubliable paysage Haussmannien—des bâtiments en grès de cinq étages, de larges boulevards inondés par la lumière de décembre, des châtaigniers bordant la chaussée. Les innombrables ponts qui traversent la Seine s’étendent devant nous sous un ciel magnifique. Nous sommes de retour à Paris. Comme toujours, c’est un sentiment merveilleux. Où se trouve le studio? C’est la question que je pose. A cinq minutes, nous dit Robin, ici, sur l’Avenue du Président Kennedy.

Un samedi après-midi à Paris—pour l’enregistrement d’une session avec le groupe, dans un studio d’une radio française construit dans les années 60, assis dans un véhicule qui descend l’Avenue du Président Kennedy, tout près de la Seine—tout cela donne soudain l’impression que quelque chose de l’ordre du destin est en train de se jouer.

Je n’ai pas établi de setlist—j’aurais dû le faire, sans doute. L’enjeu est grand. C’est une émission de radio nationale, toutes les prises seront faites en direct, pas de réenregistrement, pas de droit à l’erreur. Je m’étais dit que nous arriverions comme ça, sans rien préparer, que nous nous imprégnerions de l’atmosphère du lieu, et que nous laisserions la bonne vieille magie opérer, en choisissant les chansons selon l’inspiration du moment. Tout ce qui m’était venu à l’esprit, c’est que nous ne serions pas sur scène, mais dans un studio, en plein jour—et cela changeait tout pour nous.

Mais je suis sûr d’une chose, c’est de vouloir jouer World of Liars, rien que pour le plaisir d’entendre le beau pizzicato d’Amanda, mais aussi pour suivre jusqu’au bout de l’histoire la piste des espoirs exsangues et défaits, ce moment où ils finissent par abandonner et admettre que « ce monde n’est plus le nôtre ».

Le studio est une pièce immense au plafond élevé. Un piano à queue Steinway, un parquet en bois, de vieux et gros micros. Dusty Springfield a-t-elle jamais enregistré en ces lieux? Je m’amuse un peu avec la Telecaster, puis je prends la guitare acoustique et m’assieds. Amanda comprend intuitivement à quel point je n’ai rien préparé, et donc, lorsque quelqu’un demande une setlist, elle me dit simplement « Annonce les titres au fur et à mesure ».

Et voilà comment les choses se passent. Nous sommes sur le point de jouer, sachant que nous ne reviendrons jamais dans cette pièce. Plus jamais nous ne jouerons ces chansons de la même manière. Ce moment, c’est tout ce que nous avons.

Nous allons réinterpréter et faire revivre des chansons dans cette pièce. Des chansons d’un temps lointain semblent à nouveau ancrées dans le présent. C’est vrai, comme l’a dit Cormac—les visages s’estompent, les voix s’affaiblissent. Mais nous sommes là pour les ressusciter, c’est ce qu’ont toujours fait les chansons. Nous rappeler comment nous avons vécu, nous rappeler tout ce que nous avons perdu, tout ce qui a survécu. En quelques chansons des années entières reprennent vie. Sept musiciens. Sept chansons. Quelqu’un s’empare d’un tambourin. Bang!

Et c’est parti…

A Saturday Afternoon in Paris

December, 2012. Early days of Winter. We are driving into Paris on a Saturday afternoon to do a live recording for Vincent Théval’s Label Pop program. It’s a French public radio show with a devoted audience, 10.30 each Monday night, broadcast all over France, streamed to an international audience. We’ve just come up from Allonnes, near le Mans, where last night we played the first show of The Apartments French tour.

I’m in the back of the tour van with Amanda, Wayne and Nick. Robin Dallier, the incredible live sound guy for the tour, is driving. Only a day earlier, I discovered that when he was starting work as a young engineer, Robin was an assistant at the recording of Jane Birkin’s Amours des feintes—the last album and the last song Gainsbourg wrote. Six months later Serge would be dead.

Often Serge and Robin were alone together in the quiet of the studio earlier in the day. Over coffee, they’d smoke and chat, Serge finishing lyrics before Jane turned up to sing them. I think how the days were just beginning for Robin. For Serge, they were almost at an end.

That mood is broken as we take a fast, tilting turn, the car skips off a Périphérique exit and then there we are, in that unforgettable Haussmann landscape—five-story sandstone buildings, broad boulevards filled with December light, chestnut trees lining the road. The countless bridges that cross the Seine are spread out before us beneath a beautiful sky. We are back in Paris. As always, it feels grand. Where is the radio studio? I ask. Five minutes away Robin tells us, here on Avenue du Président Kennedy.

Saturday afternoon in Paris—a recording session with the band, a French radio studio built in the Sixties, driving down Avenue du Président Kennedy beside the Seine—all of this makes it suddenly feel like some kind of destiny is at play.

I don’t have a list of songs—I suppose I should have. There’s a lot at stake. It’s a national radio program, all the takes will be live, no overdubs, no going back. I thought we’d just turn up, get the feel for the room and leave what happens to the old, rough magic, making a set up on the spot. All I’ve thought about is we’re not on stage, it’s a studio, it’s daytime—and all of this is different for us.

But I am definite about wanting to play World of Liars, as much because I love to hear AB’s beautiful pizzicato hook as anything else and to follow the trail of exhausted, defeated hopes through to the story’s end, that place where they finally give in and admit “it’s not our world anymore.”

The studio is a huge, high-ceilinged room. A Steinway grand piano, wooden parquet floor, big old microphones. Has Dusty Springfield ever recorded here? I faff about a bit with the Telecaster, then pick up the acoustic guitar and take a chair. Amanda intuitively understands exactly how unprepared I am, so when someone asks for a set list she simply says “Just call them out.”

And that’s how it goes. We’re about to play, knowing we will never be in this room again. Never again will we play these songs the same way. This is all we have, this moment.

Songs will be revisited and relived in this room. Songs from long ago seem set once more in the present. It’s true, as Cormac said—faces fade, voices dim. But we are here to call them back as songs have always done. Remind us how we lived, remind us of all that has been lost, all that has lasted. Years condense into a set. Seven players. Seven songs. Someone picks up a tambourine. Bang!

And we begin...

INTERVIEW WITH PETER MILTON WALSH BY Pierre Lemarchand

Published in Equilibre Fragile, Indie Rock and Folk magazine

The Apartments have disappeared and been silent for long periods of time. Do you think it has shrouded the band in mystery and has made it even more special?

PMW: I can’t look at The Apartments from the outside. I can only tell you what it’s like from the inside and I’ve always found it dangerous to think about the image people have of you. You know that Arctic Monkeys album—Whatever People Say I Am, That’s What I’m Not — the title they got from Alan Sillitoe? That’s the situation. I learned very early on that it’s impossible to control or understand how people see you. A woman who was one of the publicists at Rough Trade had said to me how surprised she was when she met me, that I had a certain swagger that she said she could recognise from a mile away. That wasn’t the right word for it but I knew what she meant—that I had a kind of ease and confidence she didn’t get from other indie bands. That she wasn’t expecting. At the time, innocence was pretty much the one thing every indie band in England had in common with the other. I’d been around enough to have a different take on the world. I was older, with more experience—I’d been in and out of all kinds of cities, all kinds of lives. I’d had to survive. I think I understood the landscape of loss, mile by mile and hill by hill probably even by then, in fact.

THE SONGS ARE SIMPLE STORIES ABOUT BEING ALIVE.

With songs and bands, there are all kinds of ups and downs, there’s a cycle to these things, to being in and out of favour. So I am just lucky that people still take my songs into their lives. Because I turned my back on it, I naturally felt the music world was passing me by and I knew it and didn’t care… I felt shut out from that world where life went on.

I am always surprised that people turn up when I play and I’m very grateful that they do. It is good too that the songs mean so much to them that some are standing there in tears. As Natasha said, The Apartments can be just hell for mascara. I like to think that people sense life there, beating inside the songs. That they can feel that either they’ve lived like that or that they haven’t—but that the songs are simple stories about being alive.

And if those songs were heard only in the underground, passed between people like a secret without the kind of public attention others got, well, they still found the listeners who needed them. They became songs that someone loved. When people get them, they really get them. When they fall for them, they fall hard. That’s more than enough for me, far more than I could have expected. I wasn’t in the race even when I was in the race and I think about that kind of thing even less now. I can’t take people down Memory Lane. The Apartments slipped through the cracks there and that’s just our fate. Can’t beat the past. Can’t start anew. Can’t rewrite or regret it.

What does Peter Milton Walsh does when he does not write songs, play or record music?

PMW: Well that’s quite a lot of time taken up right there. I’m always reading, usually many books at once, watching and going to movies, listening to music. I listen to certain things at certain times, sometimes even certain days. Ravel on a Sunday morning. People say you can vacuum to Future Islands or XX—but I think everyone knows if you want to vacuum the entire house, you’ve got to have Chic playing. Maybe James Brown.

I sometimes cook. There’s no music on earth better to cook to than soundtracks. Showtunes, Great American Songbook. Musicals. I don’t bake cakes, on principle. And for the record, I think Gâteau d’Amour should only ever be baked by Catherine Deneuve.

Some soundtracks—Jerry Goldsmith’s Chinatown for instance—are very dangerous. Something about them that makes you look a little too longingly at the liquor cabinet—in which I note, rather sadly, that most of the bottles—Cointreau, Courvoisier, Bombay Sapphire—are pretty full.

Overall though, I try to keep things very simple. Simplicity and sensuality—that’s about all you need I think. I am easily overwhelmed, a bit chaotic and I’d have to say very easily distracted. The room in which I write has a piano, a wooden table with a typewriter, some bookshelves, a record player and a stack of LPs and singles. No internet. Despite that, I have days when I seem to do nothing productive at all.

You seem to and listen to new music and young artists. How do you keep yourself informed of new releases?

PMW: It happens without trying. I think you can’t help but encounter new music. Things float into the streams that are constantly running through our lives. Plus, I have a family that listens to music. A wife and teenagers, a son and daughter living at home. There’s radio in the car. Streaming, Spotify. YouTube, all the usual suspects.

Sometimes I’ll overhear something that gets to me. The first time I heard King Krule blaring from my son’s room, I thought wow, Fat City! (an Alan Vega/Alex Chilton track). I was wrong—I still like the King, though. When my son was about 12 or 13 he went through a dubstep stage, Skrillex etc at which point I did what any loving father would do—I asked him to leave home.

And of course the defining experience of being online—which is why I try to cut back on it—is that once you’re there, you’re constantly being shot like a pinball, rapidly from one thing to another. You’d have to go out of your way to avoid new songs. And I still find now that I am completely obsessive, just as I was as a child. When I find a song I love, I will play the track over & over & over. It’s the same for new music as it was when The Apartments first started. If you wanted to know what the consensus was, where the crowd was about to head, you’d read NME or maybe, Melody Maker. If I want to know now what the hive is going to be listening to soon, I’d take a look at Pitchfork, Stereogum.

How do you relate to your own records? Are you especially proud of certain songs, of certain records?

PMW: I’ve learned—only in the past 10 years actually, and only after I’d slammed a door on the public, stopped playing and touring so long ago—that there’s something of you in every song you’ve written and that often you can recognise the person who wrote them, but only as a distant stranger. Often you recognise them with regret. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve felt about my own work—Someone wrote these songs, someone who resembled me. Where is he now? He has gone away. Songs use you up. Use your life up. It vanishes into them.

I do like No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal for various reasons. Because it’s the most recent. Because it was a struggle, but I got through it. Because I thought I’d never make another record again. Because I see it as less of as a record than as a memorial. I like it because I tried new and different things. No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal; Swap Places—they’re just 2 chord songs.

I like that I played the piano on it. I like it because I didn’t strum the guitar the way I usually do, but played it like Peter Green on Albatross, one stroke for each chord. I like it because of Twenty One, which by the way has only 3 chords too. It was all a bit of a breakthrough for me. And I like it because the title track was the one I wrote last, just before I went into the studio. In the Tourneur movie, Out of the Past, the main guy Jeff says at one point,“My feelings? About ten years ago, I hid them somewhere and haven’t been able to find them.” I did not want to be that guy anymore, the one who went inside himself and never emerged again. I didn’t want to that guy driving through the rain wondering where the good luck went.

I was surprised the record went down so well. Because it’s not the most upbeat collection of songs. But—you have what you’ve been dealt. When someone asks “What was it like?”, the story you bring back is the answer. You tell it how you can, you can’t dress it up to be more acceptably hopeful.

As for my older records, well I’ve gotten used to the fact that with each new record, the artist runs the risk of leaving people behind. Some people thought I never made a right move after the first EP. Some that we lost it after “the evening visits…”. Some think we will never equal drift. Some that A Life Full of Farewells says it all, the others you can forget. Some think apart was the high point we’d been heading towards. So, you just learn to live with this and if people drop away, people drop away.

Luckily, every Apartments album has its loyalists. Not everyone likes the same ones with the same passion, but each of them has found a place in someone’s lives. But the other good thing is that The Apartments seem to be always generating new fans too.

You seem very fond of performing live. Is it frustrating not to tour more often ? Do you miss playing for your fans more often?

PMW: I’m lucky that people who were new to The Apartments and new to the songs, new to me came along and felt that the live shows meant something to them as well. That they’re somehow memorable. I was pretty terrified about how the shows would go. I mean we were playing a full set of new songs, the new album. The band had never played them before and all of it was definitely making me anxious in the months beforehand.

But, I have a friend who’s a skier, and when she was telling me about some of the runs she’d done, I said she must be fearless. She said no, we’re full of fear. We just don’t let the fear stop us. Great advice. And I was very lucky with this band—I met up with Natasha and Antoine first, they played the whole No Song, No Spell perfectly, so I felt right then that it was going to work.

And I knew that Fab, and Eliot and Nick were just brilliant. We were very very lucky. The one weak link in this whole thing was always going to be me! And when you play live, songs—anyone’s songs—can draw people together into a kind of intimacy which can happen only then and there in the room. For some, it is unforgettable.

I LIKE THE FACT THAT YOU LOSE YOURSELF PLAYING LIVE.

But I like the fact that you lose yourself playing live. I have a very different take on this to say, Joanna Newsom or Sufjan, in that ‘live’ for me is always about being completely in the moment. Those beautiful note-perfect arrangements that JN and Sufjan do are the same in every room, on every night, for every audience. I have a different way of playing live.

When you play live, one of ‘you’ disappears, another ‘you’ emerges. The ‘I’ who writes the song, the ‘I’ who sings it, is another. You disappear into the time you are singing, you are fully present in it and you are purely you—but then you emerge on the other side when the show is over as if it were a dream, but there is some evidence that it happened. It’s as if you wake from the dream and there you are, suddenly back in that other practical world of cares and concerns. The other has vanished. “I feel myself inhabited by a force or being—very little known to me. It gives the orders; I follow” Cocteau said. But it’s that beautiful lapse of thinking, forgetting about yourself, that is promised by both the creative and the sensual life. That’s the rainbow’s end we’re always after. Always.

Why did you choose Microcultures to release No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal? To be close to your fans? To stay independent ? Because you distrust traditional labels? Because it’s French ?

PMW: I made this record long before I knew if anyone would release it or if anyone would get to hear it. I made it because I had to. I thought of it not as the next record but the last. But once I made it, I began to think about all the people I’d met on the Autumn 2012 tour who said to me they were looking forward to a new album. I felt I owed it to these people, the ones who cared for the songs, should at least be offered them and MC was the best way to reach them I think.

I think my mind is just set in that one last roll of the dice way of thinking. And since I was, for good reason, out of the game for the longest time, I thought the fact that people were even interested was a miracle. Who would have thought, this far down the road, such a thing was possible? And while I think people realise what it took to get here, with this album, what it took personally, I have believed my entire life that songs are never just one person’s story, that people can see themselves reflected in the songs.

Pierre Lemarchand

Equilibre fragile, DIY Magazine and Label

November 2015

entretien avec PETER Milton Walsh PAR PIERRE LEMARCHAND

Publication originale dans Equilibre Fragile (magazine rock et folk indépendant)

Pensez-vous que la rareté des disques de The Apartments (rareté souvent contrainte, et non le fruit de choix délibérés) soit finalement une force? Cette rareté n’entoure-t-telle pas le groupe d’un mystère, d’un atypisme, d’une certaine préciosité?

PMW: Ca m’est difficile d’avoir un point de vue extérieur sur The Apartments. Je peux juste te parler de ce que je ressens de l’intérieur. J’ai toujours trouvé ça dangereux de penser à la façon dont les gens te voient. Tu connais peut-être l’album des Artic Monkeys, Whatever people say I am, That’s what I’m not, une phrase empruntée à Allan Sillitoe (1) ? Eh bien, c’est exactement ça. J’ai appris très tôt qu’il était impossible de contrôler ou de comprendre la manière dont les gens te perçoivent. Je me souviens d’une attachée de communication à Rough Trade (2) qui m’a dit qu’elle avait été surprise, la première fois que je l’ai rencontrée, de voir que je roulais des mécaniques. Je ne crois pas que ce soit vrai mais je vois ce qu’elle voulait dire : j’avais une confiance en moi que les autres musiciens indépendants n’avaient pas. A l’époque, les groupes indé en Angleterre avaient tous une certaine innocence. J’étais plus vieux et j’avais plus d’expérience. J’avais habité dans plein de villes différentes et j’avais eu plusieurs vies. Je savais, au plus profond de moi-même ce que c’était de perdre quelqu’un.

THE APARTMENTS N’EST PAS UN GROUPE À MASCARA.

En musique il y a des hauts et des bas, des cycles, des modes. J’ai de la chance car mes chansons font toujours partie de la vie des gens. Comme je lui avais tourné le dos, je pensais que le monde de la musique allait m’oublier mais je m’en moquais…. Je suis toujours agréablement surpris de voir des gens à mes concerts et j’en suis très reconnaissant. Que mes chansons les touchent autant, que certains les écoutent les larmes aux yeux, est quelque chose de très important pour moi. Comme le dit Natasha (3), The Apartments n’est pas un groupe à mascara. Qu’ils aient vécu ce que j’ai vécu ou pas, je me dit que les gens perçoivent toute la sincérité que j’ai mis dans ces chansons. Ils savent qu’elles parlent tout simplement de la vie.

Et même si ces chansons n’ont jamais touché le grand public, même si elles ont circulé comme sous le manteau, ceux qui les ont écoutées les ont aimées. Ceux qui les comprennent les comprennent vraiment. Ceux qui les aiment les aiment par-dessus tout. Même dans mes rêves les plus fous je ne pouvais en demander plus. Je ne courrais déjà pas après le succès du temps où j’avais un certain succès, et à présent cela m’importe encore moins… Je ne peux pas ramener les gens sur les chemins du passé. The Apartments sont passés au travers des mailles du filet, et tel était leur destin. On ne peut pas vaincre le passé, ni repartir de zéro. Il n’y a donc aucun regret à avoir.

The Apartments ne semblent s’épanouir que dans les ellipses et leur musique générer de longs silences ; que fait Peter Milton Walsh quand il ne compose pas, ne joue pas, n’enregistre pas?

PMW: Je passe mon temps à lire; je lis souvent plusieurs livres à la fois. Je vais au cinéma, je regarde des films chez moi, j’écoute de la musique. Il y a des musiques que j’écoute à certains moments de la journée, certains jours de la semaine. Ravel, c’est le dimanche matin. On dit que Future Islands ou XX c’est bien pour passer l’aspirateur, mais si vous devez nettoyer toute la maison, Chic ou même James Brown sont bien meilleurs.

Ça m’arrive de cuisiner. Il y a rien de mieux pour faire la cuisine que les B.O. de films. Des chansons des spectacles musicaux, les standards du Great American Songbook (4). Par principe, je ne fais pas de gâteaux. Et soit dit en passant, je pense que le Gâteau d’Amour (5) ne devrait être cuisiné que par Catherine Deneuve en personne.

Certaines B.O., comme le musique de Chinatown de Jerry Goldsmith par exemple, sont très dangereuses. Elles te donnent un peu trop envie d’ouvrir une bonne bouteille!

J’essaye d’avoir une vie simple. Simplicité et sensualité sont tout ce dont j’ai besoin. Je dois cependant avouer que je suis souvent débordé, désordonné, et que je me laisse déconcentrer un peu trop facilement. Dans la pièce où j’écris, il y a un piano, une table en bois avec une machine à écrire, des étagères remplies de livres et des tonnes d’albums et de 45 tours. Pas d’internet. Malgré tout ça, il y a des jours où je ne produis rien du tout.

Vous semblez très attentif à ce qui se fait aujourd’hui en musique, aux jeunes artistes… Comment vous tenez-vous au courant?

PMW: Ça arrive naturellement. On ne peut pas s’empêcher de découvrir de nouvelles musiques. Elles sont des courants qui traversent constamment nos vies. De plus, j’ai une famille, une femme, deux adolescents (un fils et une fille), qui vivent encore à la maison et qui écoutent de la musique. J’ai un autoradio dans la voiture, Spotify, YouTube comme tout le monde. De temps en temps une chanson attire mon attention. La première fois que j’ai entendu mon fils écouter King Krule à fond dans sa chambre, je me suis dit : « Cool, Fat City » (une chanson d’Alan Vega et Alex Chilton) 6. Je me suis trompé… Ceci dit j’aime toujours le King. Lorsque mon fils avait 12 ou 13 ans, il y avait un moment où il écoutait du dubstep (Skrillex, etc.) toute la journée. J’ai fait ce qu’un père aimant doit faire: je lui ai demandé de prendre ses affaires et de quitter la maison.

Et bien-sûr quand tu es sur internet tu ne sais pas où donner de la tête. Tu dois faire un effort pour ne pas découvrir de nouvelles chansons. Je me rends compte que la musique m’obsède autant que quand j’étais enfant. Quand je découvre une chanson qui me plaît, je l’écoute en boucle. Au début de The Apartments, si tu voulais savoir ce qui était populaire ou ce que serait la nouvelle tendance, tu lisais le New Musical Express ou le Melody Maker. C’est pareil aujourd’hui: si je veux savoir ce ce qui s’écoute dans la blogosphere, je jette un coup d’œil à Pitchfork ou à Stereogum.

Quel rapport entretenez-vous avec vos propres disques ? Y a-t-il des chansons dont vous soyez particulièrement fier ? Ou un disque?

PMW: C’est seulement récemment, au cours des dix dernières années, après avoir arrêté de tourner, que je me suis rendu compte que l’on met quelque chose de nous-même dans chaque chanson que l’on écrit et que l’on peut reconnaître celui qu’on était quand on a écrit la chanson. Mais il y a comme une distance. Il y a souvent aussi du regret. J’ai cessé de compter le nombre de fois où je me suis dit à propos d’une de mes chansons : « Celui qui a écrit cette chanson me ressemble. Où est-il passé ? Il a disparu. » Les chansons se nourrissent de vous, de votre vie, et l’absorbent à jamais.

J’aime beaucoup l’album No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal pour plein de raisons différentes. Parce que c’est le plus récent. Parce que ça a été une lutte, que j’ai finalement emportée. Parce que je pensais que ce serait mon dernier. Parce que je le vois moins comme un album que comme une ode à la mémoire de quelqu’un. Parce que j’y ai lancé de nouvelles pistes : No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal et Swap Places sont des chansons construites sur seulement deux accords. Je l’aime car j’y joue du piano. J’aime cet album car je n’ai pas gratté ma guitare comme je le fais d’habitude mais ai joué à la façon de Peter Green sur Albatross (7): un seul battement pour chaque accord. Je l’aime à cause de Twenty One qui, soit dit en passant, est une chanson avec seulement trois accords. Tout cela a constitué pour moi une sorte de révolution. Enfin j’aime ce disque parce que la chanson qui a donné son titre à l’album a été composée en dernier, juste avant d’entrer en studio.

Dans le film de Tourner, Out Of The Past (8), le personnage principal Jeff dit à un moment: « Mes sentiments? Il y a dix ans de cela, je les ai cachés quelque part et n’ai jamais su les retrouver depuis. » Je ne voulais pas être ce mec qui s’est coupé du monde et qui n’est jamais revenu. Je ne voulais pas être ce mec qui conduit sous la pluie et se demande pourquoi la chance de lui sourit plus (9).

Ca m’a vraiment surpris que le disque soit si bien accueilli. Parce que ce n’est pas l’album le plus optimiste du monde. Mais bon tu ne choisis pas ton destin. Et quand quelqu’un vient te demander : « Comment as-tu pu vivre ça ? », l’histoire que tu lui rapportes constitue la meilleure des réponses. Tu la racontes comme tu peux. Et tu ne peux pas l’enjoliver en espérant qu’elle passera mieux.

En regardant en arrière, j’ai accepté le fait qu’à chaque album un artiste prend le risque de perdre des fans en route. Certains pensent qu’on n’a rien fait de mieux que notre premier EP. D’autres que l’on s’est fourvoyés après the evening visits… D’autres pensent qu’on n’arrivera jamais à égaler Drift. Certains fans disent qu’on a tout dit dans A Life Full Of Farewells et que l’on peut oublier tout le reste. Pour d’autres, enfin, Apart est le sommet que nous ne pourrons jamais dépasser. S’il faut perdre des gens en route, c’est comme ça : il faut l’accepter. Ce qui est bien en revanche c’est que chaque album de The Apartments a ses défenseurs. Personne n’aime les disques du groupe avec la même intensité, mais chacun d’entre eux a su trouver sa place dans la vie de tas de gens. Et l’autre bon côté, c’est que The Apartments parviennent à toucher de nouveaux fans à chaque fois.

Vous semblez apprécier de jouer en concert. Si c’est bien le cas, ces longs silences ne sont-ils pas douloureux, ne génèrent-ils pas une frustration, un manque, une souffrance ? Etre privé de ce contact avec votre public n’est-il pas difficile ?

PMW: Il y a des gens qui ne connaissaient pas The Apartments, ni nos albums, qui sont venus aux concerts et qui ont été touchés. On a eu beaucoup de chance. J’étais terrifié à l’idée de partir en tournée. Parce qu’on allait jouer un nouveau set et défendre le dernier album. Le groupe n’avait jamais joué les nouvelles chansons, et cela m’a vraiment angoissé durant les mois qui ont précédé la tournée. Je me souviens avoir dit à une amie skieuse, lorsqu’elle me racontait ses descentes, qu’elle était intrépide. Elle m’a répondu que non, que tout le monde avait peur. On doit juste l’empêcher de nous submerger. Très bon conseil. Et j’ai eu beaucoup de chance d’avoir ce groupe avec moi. Dans un premier temps, j’ai travaillé avec Natasha et Antoine qui ont joué à la perfection l’intégralité de No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal. Là, j’ai senti que tout aller fonctionner, d’autant que je savais que Fab, Eliot et Nick (10) sont des musiciens fantastiques. Oui, beaucoup, beaucoup de chance… Le maillon faible, s’il devait en avoir un, ça allait de toute façon être moi.

En tournée, les chansons – n’importe quelles chansons – créent une intimité entre les gens, une intimité qui ne peux se créer que dans le ici et le maintenant du concert. Et en cela, c’est inoubliable.

J’AIME ME PERDRE EN CONCERT.

A la différence de Joanna Newsom ou Sufjan Stevens, pour moi, faire un concert c’est être complètement dans le moment présent. Les notes que jouent Joanna Newsom et Sufjan Stevens, les arrangements qu’ils composent, sont superbes mais sont les mêmes quels que soient les concerts et les lieux où ils jouent. J’ai une autre façon d’appréhender le live. En concert, il y a un « moi » qui disparaît et un autre « moi » qui apparaît. Il y a le « moi » qui a écrit la chanson et le « moi » qui la chante. Tu disparais dans le ici et le maintenant du concert, et tu es en même temps totalement présent au monde, tu es absolument toi-même. Et, à la fin du concert, c’est comme si tu te réveillais du rêve, tout en sachant que tout cela était bien réel.

Tu redécouvres le monde, avec son lot de soucis et de difficultés. L’autre monde a disparu. Cocteau disait qu’il se sentait habité par une force qui lui était inconnue, qui lui donnait des ordres et à laquelle il obéissait (11). C’est beau cette façon que l’on a de se perdre dans l’acte créatif. On arrête de penser. C’est comme la sensualité. Tout le monde court après. Absolument tout le monde.

Pourquoi avoir fait le choix de Microcultures pour publier le disque No Song No Spell No Madrigal ? Un souci de proximité avec votre public ? Une volonté d’indépendance par rapport à l’industrie du disque ? Une défiance quant aux labels traditionnels ? Le choix de la France?

PMW: J’ai fait ce disque bien avant de savoir si s’il serait publié et si quiconque l’écouterait un jour. Je l’ai fait car je devais le faire. Je l’imaginais non comme mon prochain disque, mais comme l’ultime. Mais une fois qu’il a été réalisé, je me suis mis à penser à tous ces gens que j’avais pu rencontrer lors de la tournée de l’automne 2012 et qui m’avaient confié espérer un nouveau disque de The Apartments. Je me suis dit que je devais donner, à toutes ces personnes pour qui ma musique comptait, la possibilité d’entendre mes nouvelles chansons. Il me semble que Microcultures était le meilleur moyen de pouvoir toucher tous ces gens.

« Un dernier coup de dés » : voilà où j’en était. Et comme, pour des raisons bien compréhensibles, je m’étais retiré du jeu pendant si longtemps, il m’est apparu miraculeux que ça puisse intéresser quelqu’un. Qui aurait pu penser, avec le recul, qu’une telle chose puisse arriver ? Et je sais que les gens se rendent compte ce que ça m’a coûté pour en arriver là, avec cet album, ce que ça m’a coûté personnellement. Cela me renforce dans la conviction que les chansons ne sont jamais que l’histoire d’un individu, mais que chacun peut se voir dans leur reflet.

Pierre Lemarchand

Traduction : My North Eye & Pierre Lemarchand

Equilibre fragile, DIY Magazine and Label

Novembre 2015

1 « Quoique les gens disent sur moi, c’est ce que je ne suis pas ». Alan Sillitoe est un écrivain britannique qui évoqua dans ses livres les classes populaires (Samedi soir, dimanche matin -1958, la Solitude du coureur de fond – 1959).

2 Rough Trade est le label anglais qui signa le premier album de The Apartments, The Evening Visits…

3 Natasha Penot, du groupe français Grisbi, chante au sein des Apartments sur le disque et la tournée « No Song No Spell No Madrigal ».

4 Le grand répertoire de la chanson américaine des années 20 à 50, c’est-à-dire avant l’arrivée du rock’n’roll

5 Le Gâteau d’Amour est cuisiné par Catherine Deneuve dans le film Peau d’Âne de Jacques Demy.

6 Chanson extraite du disque co-signé par Alan Vega, Alex Chilton et Ben Vaughn, Cubist Blues (Thirsty Ear, 1996)

7 Peter Green était le guitariste de Fleetwood Mac. Peter Milton Walsh fait ici référence au morceau instrumental Albatross que le groupe faisait paraître en 1968 sur un 45 tours sous label Blue Horizon.

8 Out Of The Past, avec Robert Mitchum et Jane Greer, a été réalisé par Jacques Tourneur en 1947.

9 Peter fait référence aux paroles de sa chanson No Song, No Spell, No Madrigal (« Don’t wanna be that guy / Driving through the rain / Wondering where the good luck went »)

10 Eliot Fish (basse), Nick Allum (batterie), Fabien Tessier (claviers), Antoine Chaperon (guitare) et Natasha Penot (chant) constituaient avec Peter la formation des Apartments lors de la tournée française d’automne 2015.

11 Voici la citation originale de Jean Cocteau à laquelle Peter fait référence : « Les poètes ne sont que les domestiques d’une force qui les habite, d’un maître qui les emploie et dont ils ne connaissent même pas le visage qui n’est peut-être que le leur. »

the evening visits…and stays for years. Notes by Robert Forster (The Go-Betweens)

for captured tracks 2015 reissue of the evening visits…

In the small but vibrant Brisbane punk/new wave scene of the late Seventies, it seemed that everyone knew or knew of everyone else. Peter Milton Walsh, though, was someone that fellow Go-Between Grant McLennan and I had heard of before we had met him. The mysteries and myths that loom large over the man and his music didn’t begin on early Eighties New York rooftops or in Sydney terraced houses or during Summer days at Keats Grove by Hampstead Heath. There they were enhanced but Peter, from first acquaintance, came with whispers and claims on his trail—a princely person more formed than most, certainly more than Grant and I.

We asked him into The Go-Betweens when a world wide contract was waved at us and he played some great guitar on recordings we made. His band, however, was The Apartments. Peter was always a leader, and his group was alive and dangerous from the get-go. Grant and I saw most shows they did in their first incarnation, when the freshly written Help and Nobody Like You were performed. It was a time when everything could be clocked, when every good song that anyone in town had was known to us, and these songs were in direct relation/competition to what we thought were the very best of our own. It’s such a small world, I saw it first. Baby begs for kisses, all on Sunday. These and other lines rang out and were received. There was another pop-poet in town; a band and a songwriter feeding on the small, static scene and aware that there was more to music, more to life, than that which might be gained from the latest Buzzcocks single. The Apartments, Act I, were a sight to behold.

Then things got foggy. Travel. New cities. Brisbane had two good years of energy in it but no more. The Go-Betweens crept on, The Apartments stopped, Peter as indomitable spirit remained. He was ghostly. A correspondent through letters, someone you saw for a night only to then vanish. Again he became a person of heroic unseen exploits, head shaking stuff that got passed around kitchens and bars. His music was fracturing and growing, which continued a symbiosis between himself and The Go-Betweens, as we both tried to attach new feelings to new music.

This was difficult—a world was trying to be invented but a lack of money and recognition conspired against it. Everybody who was pushing was struggling. And the times when Grant, Lindy and I did wonder how and why to go on—a new song, a visit, a letter or a quote would come through from Peter, and the three of us, with inspiration again in pocket, would turn back to the crusade.

Which is why in Eastbourne in late ’82, when The Go-Betweens were recording Before Hollywood, Grant could easily ask me, “Can you help with a lyric to this song? It’s about Peter Walsh”. (An historical note. Peter Milton Walsh would have to be the only person of male gender to inspire two Go-Betweens songs—That Way, just mentioned, and Don’t Let Him Come Back)

CAN YOU HELP WITH A LYRIC TO THIS SONG? IT’S ABOUT PETER WALSH

All You Wanted was Peter’s return to The Apartments, to songs, to sha-la-la. It’s no surprise that this number and others destined for the evening visits…and stays for years were written during a long sojourn in New York. Peter was of a New York State Of Mind; his adhesion to the city not just through the Brill Building/Commander Lou Reed/scratch and electricity of 70s CBGB’s axis, but to a time before, of Moon River and Capote, Andy before the soup cans—and Sinatra. After all, the band was named after a Billy Wilder film—and the best Wilder film at that.

My favourite cuts today, (it may change tomorrow—light rain would immediately turn me to All The Birthdays and Speechless With Tuesday), are the pop songs—What’s The Morning For? and Great Fool, the latter with its The ki-i-ind who ke-e-eep the wo-or-orld al-i-ight chorus, the philosophical cri de couer of the album. Day comes up sicker than a cat, off Mr Somewhere is of course, one of the best opening lines of all time. Grant and I took note, and from mid-1985 on the lesson was put into practice; the beauty and impact of first lines had to be improved.

The instrumentation on the album was rich, and one of the reasons why the record has lasted. There are many more things to be said in praise of the songwriting and the impassioned singing, but I shall leave that to the scholars. I am a fan—and it’s wonderful to be reacquainted with the album.

Robert Forster

Geiselhöring, Bavaria

January, 2014

the evening visits… and stays for years

NOTES BY ROBERT FORSTER (THE GO-BETWEENS)

Traduction française de Richard Robert—compositeur, chanteur, critique musical (Les Inrockuptibles, L’Oreille Absolue), programmateur des Nuits de Fourvière (Lyon)

A la fin des années 70, les groupes punk et new wave de Brisbane formaient une scène modeste mais vibrante, où tout le monde semblait, de près ou de loin, se connaître. Mais Peter Milton Walsh, lui, était quelqu’un dont mon camarade des Go-Betweens Grant McLennan et moi-même avions entendu parler avant même de l’avoir rencontré. Pour éclore, les mystères et les mythes planant au-dessus de cet homme et de sa musique n’allaient pas attendre les toits du New York du début des années 80, les rangées de maisons de Sydney ni les journées d’été passées à Keats Grove, près de Hampstead Heath. En ces lieux, ils allaient certess’ épaissir; mais lors de notre première rencontre, Peter traînait déjà dans son sillage son lot de cris et de chuchotements – il était cette personne à l’élégance princière, plus mature que la moyenne, en tout cas bien plus que Grant et moi pouvions l’être.

Nous lui demandâmes d’intégrer The Go-Betweens alors qu’on nous agitait un contrat international sous le nez, et il joua de superbes parties de guitare sur nos enregistrements. Mais son groupe à lui c’était The Apartments. Peter était un leader à plein temps, et son groupe avait été un concurrent actif et très sérieux dès le départ. Grant et moi avions vu la plupart des concerts que le groupe, dans sa première mouture, avait pu donner, quand il jouait les tout frais Help ou Nobody Like You. C’était une époque où l’impact de toute chose pouvait vite être mesuré, où toute nouvelle bonne chanson de n’importe quel songwriter en ville nous était connue, et entrait directement en corrélation/compétition avec ce que nous estimions être nos propres morceaux de bravoure. “It’s such a small world, I saw it first”. “Baby begs for kisses that fall on Sundays”. Parmi tant d’autres,ces vers auront résonné et capté l’attention. Un nouveau poète pop était en ville ; un groupe et un songwriter se nourrissant de cette petite scène stagnante, conscients que, dans la musique comme dans la vie, il y avait bien plus à entrevoir que ce qu’on pouvait gagner à l’écoute du dernier simple des Buzzcocks. The Apartments, acte premier, valait sacrément le coup d’œil.

Et puis les choses s’embrouillèrent. Des voyages. De nouvelles villes. La belle énergie de Brisbane dura deux ans, puis s’évanouit. Les Go Betweens avançaient sans fracas; The Apartments s’arrêta; Peter, tel un esprit indomptable, était toujours là. Il devint fantomatique. Un correspondant épistolaire, un compagnon d’un soir qui disparaissait aussitôt. Il était à nouveau cet homme capable d’exploits héroïques dérobés à la vue du nombre, de morceaux jubilatoires qui circulaient de bars en cuisines. Sa musique était à la fois en rupture et en développement, prolongeant la symbiose avec The Go-Betweens—puisque nous tentions nous aussi de rattacher de nouveaux sentiments à une nouvelle musique.

C’était une période compliquée—un monde tentait des’inventer, mais le manque d’argent et de reconnaissance se liguait contre lui. Quiconque essayait de percer était en difficulté. C’est dans les moments où Grant, Lindy et moi nous demandions comment et pourquoi continuer, que nous recevions une nouvelle chanson, une visite, unelettre ou une phrase de Peter ; et tous trois, de l’inspiration à nouveau plein les poches, repartions alors en croisade.

Voila pourquoi, fin 1982, à Eastbourne, alors que les Go Betweens enregistraient Before Hollywood, Grant vint en toute simplicité me demander: “Pourrais-tu me donner un coup de main sur les paroles de cette chanson? C’est à propos de Peter Walsh”. (Fait historique: Peter Milton Walsh restera la seule personne de sexe masculin a avoir inspiré deux chansons des Go-Betweens—That Way, évoquée à l’instant, et Don’t Let Him Come Back)

POURRAIS-TU ME DONNERUN COUP DE MAIN SUR LES PAROLES DE CETTE CHANSON ? C’EST À PROPOS DE PETER WALSH

All You Wanted marqua le retour de Peter à The Apartments, aux chansons, au sha-la-la. Il n’est guère surprenant que ce morceau et d’autres, destinés à the evening visits…and stays for years, furent été écrits lors d’un long séjour à New York. Peter avait l’Etat d’Esprit New Yorkais; son attachement à cette ville ne se résumait pas à l’axe reliant le Brill Building, le Commandant Lou Reed et les griffures électriques du CBGB des seventies: il remontait à une époque plus lointaine, celle de Moon River et de Capote, d’Andy avant ses boîtes de soupe – et de Sinatra. Après tout, le groupe avait tiré son nom d’un film de Billy Wilder—et le meilleur film de Wilder, avec ça.

Mes morceaux favoris aujourd’hui (il est possible que cela change demain—une pluie fine me ramènerait immédiatement vers All The Birthdays et Speechless With Tuesday) sont les chansons pop—What’s The Morning For et Great Fool, cette dernière avec le “The ki-i-ind who ke-e-eep the wo-or-orld al-i-ight” de son refrain, le cri du cœur philosophique de l’album.

“Day comes up sicker than a cat”, sur Mr Somewhere, est bien évidemment l’un des plus grands incipits de tous les temps. Grant et moi en prîmes note, et à partir de 1985, la leçon fut retenue et appliquée ; la beauté et l’impact des premières lignes se devaient d’être perfectionnés.

L’instrumentation sur cet album est riche, et c’est l’une des raisons pour lesquelles il n’a pas vieilli. Il y aurait tellement d’autres louanges à dresser en l’honneur de ce songwriting et de ce chant tout en ferveur, mais je vais laisser cela aux spécialistes. Je suis un fan, et il est merveilleux de redécouvrir ce disque.

Robert Forster

Geiselhöring, Bavière

Janvier 2014

I Thought It Put A Stop To Songs Forever

First issue in Mess+Noise (online magazine)

After completing The Apartments’ fifth album in the 1990s, Peter Milton Walsh watched in horror as his life echoed the darkest portent of his lyrics. In the midst of a gradual return following a decade’s absence, the revered Brisbane songwriter recounts for ANDREW STAFFORD the making of 1997’s underrated apart and the personal tragedy that changed him forever.

Peter Milton Walsh was on a roll. It was 1996, and the singer-songwriter behind The Apartments – who had emerged from the same post-Saints Brisbane scene that gave birth to The Go-Betweens and The Riptides – was onto his fourth album in four years. drift, fête foraine and A Life Full of Farewells had all met with acclaim, and if they hadn’t done a great deal to boost his reputation in his home country, they’d cemented it in Europe.

Prior to this, Walsh had spent much of the 1980s “like a scrap of paper, blown down the windy streets of the world.” He’d had a couple of real successes: the haunting, cello-soaked elegy Mr. Somewhere, from The Apartments’ 1985 Rough Trade album the evening visits…and stays for years, was later covered by 4AD’s shape-shifting ensemble This Mortal Coil. Another song, The Shyest Time, appeared in the John Hughes film Some Kind of Wonderful at the height of Hughes’ fame. “Sometimes it seemed like I got one lucky break after another and I didn’t hold onto any of them,” he says. “Fugitives might have had more stability.”

Finally, though, life had settled, and it was good. Walsh was working a straight but rewarding job in Sydney, anchored by his wife and their young son Riley. Around that, he had constructed an alternative existence as a recording artist that was almost clandestine. Being recognised in Europe before Australia had its advantages. “If you offered me the choice of whether to be unknown here or unknown in Europe, I admit I would go for unknown here,” Walsh says. “Having that distance has enabled me to live very quietly – lead a double life, even a secret and quite fine one here.”

Songs were flowing. The new album would be different, as different as each had been from their immediate predecessors. Three short, piano-based snippets – Doll Hospital, Your Ambulance Rides and Place of Bones – linked eight major pieces with rich, almost baroque arrangements. “I’d written not only the songs but some string, woodwind, brass and piano parts, and I just wanted to try something I never had before,” he says. “We all get restless. Sometimes we get tired of ourselves.”

A WORLD EXISTED SOMEWHERE IN WHICH THE SONGS WOULD DEEPLY CONNECT

To play these songs, Walsh needed a new band. He met Gene Maynard, a drummer who “had such fantastic swing.” He then contacted The Cruel Sea’s Ken Gormley, “a great, instinctive player with a beautiful feel. I was very surprised when I asked and he said yes.”

The result was Walsh’s least-known but quite possibly best album, apart. A lush, moving piece of work, it was also the last record Walsh would make until last year’s single Black Ribbons. There had been a 15-year silence. “I always had a hunch that what I did might appeal to a particular sensibility, that a world existed somewhere in which the songs would deeply connect,” he says. apart, perhaps, is a world unto itself. It’s a shame more people in this one haven’t heard it.

Which is not to say that the album is difficult or self-indulgent. It is merely singular. After Doll Hospital – a slightly jarring 26 seconds of a few repeated piano notes – there’s barely a pause before a low, melancholy blast of trumpet introducing No Hurry. It sounds like a foghorn blowing across a bay, and Walsh is being carried along like one of the those scraps of paper. “The days are getting longer,” he croons, backed by loping groove from Gormley. “Night comes down so late.”

“I wanted to get some of that slow sensuality of summer into a song,” Walsh says in hindsight, and perhaps it’s a metaphor for Walsh’s old hometown of Brisbane: “I got no ambition, I’ll sleep by the lazy river/Someone slowed the whole world down, in the old town called the past…” The music matches the lyric, the semi-orchestral arrangement never cluttered, “drifting along just like smoke.”

Breakdown in Vera Cruz ascends from peak to peak, piano and percussion driving the verses, trumpet and strings holding up a majestic chorus. But underneath the song is desperately sad, a story of a dissolute but codependent coupling: “They talked a little bit/Then things just went all quiet again/What they have’s on the skids/He depends on her, she depends on gin.” A drawn-out coda ends with a shiver of cello and violin.

Something to Live For is about marriage, fatherhood and letting go of the past. At the time, Walsh was writing the album three days a week and spending the other two with Riley. Playing music isn’t that important in the greater scheme of things: “Travelling man, a travelling band, the lights go out one by one/A daddy does what he has to do, the circus moves on.” “Learning the meaning of gratitude,” Walsh explains. “Trying to be good.” It’s the most optimistic, uplifting song on apart.

Things take a left turn with the appearance of Walsh’s longtime fan Dave Graney, doing his best Philip Marlowe impression as he narrates the tone poem ‘Welcome to Walsh World’. Gently brushed drums, more strings and lyrics that would do Lou Reed at his most narcissistic, early-’70s best proud. If there’s a parallel to be made here, conscious or otherwise, Apart might be likened to an Antipodean equivalent of Berlin, Reed’s bleak masterpiece of domestic melodrama.

The second half of the album opens with Friday Rich/Saturday Poor. It was an old tune for Walsh, having been demoed in 1990. After apart’s release in France, Lanvin, which was launching a new perfume, came close to using this song in an advertising campaign throughout Europe – I imagine it was the seductive introductory flourish of violin that they were after. Walsh demurs: “I liked to tell myself it was because of the prospect of decadence within the lyrics.” Lanvin ended up going with a track by Finley Quaye instead. “I’m sure the perfume sank without a trace; that wouldn’t have happened with Friday Rich,’” the author deadpans.

World of Liars is a big, slow ballad in an album that seems full of them, but it’s the sparest – no strings or brass this time, just the core of Walsh on piano, accompanied by Gormley and Maynard, with some deft hand percussion. Cheerleader underscores a more unexpected influence: the Bristol sounds of Massive Attack, Portishead and Tricky, who is name-checked in No Hurry. It’s a showcase for Gormley in particular, whose descending bass line provides the hook of a song that relies on atmosphere more than structure.

All this is leading up to Apart’s final statement. Everything’s Given to Be Taken Away opens in a similar manner to No Hurry, and reprises some of its lyrical themes of wasted potential: “There’s a rose that blossoms in the barrel/For each lost little girl.” It begins with just piano chords and the soft sound of Walsh’s voice before Gormley and Maynard enter, drawing the song out. Strings rush in like the climactic moment in The Beatles’ A Day in the Life, until finally the song explodes into a chorus of ba-ba-ba’s that’s at once childlike and exquisitely wistful.

And then, it all became horribly prophetic. On the final day of mixing, Walsh took a phone call from his GP. “Riley’s blood tests had come back,” Walsh remembers. “‘You have to take him to the Westmead Hospital right now,’ she said. ‘Right now?’ I asked. ‘Straight away – I’ve rung, and told the specialist you’re coming.’

“What got to me was the songwriter’s fear; firstly that the songs are omens, finally that the songs have come true.” Riley used to sing along to those ba-ba-ba’s; the three instrumentals, with their haunted titles, had also been floating around for some time, long before there was an inkling of anything being wrong. “The fact that I wrote such a song, and that I wrote it before things came to an end — before we lost Riley – that stopped me, and I thought it put a stop to songs forever,” he says. “I didn’t know if I could find my way back to who I was before he died, but really, I didn’t think I should, either.”

It would be over a decade later before The Apartments would re-emerge: firstly with a discreet run of shows in Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney, followed by a gig in Paris a couple of years later. With no advertising or press support, the night was a sellout, as was another rooftop set in Paris last year, at the invitation of a French magazine. “A journalist who came along, some girl who said she’d never heard of me until she found World of Liars on YouTube … said, ‘How do you explain this?’ … I had to tell her I don’t do explanations and I never question this, because it might imperil it. I am happy to do what I do in the glow of this benevolent mystery.

“I remember the record company warning me when I refused to tour to promote apart: ‘No one knows where you’ve gone or why … People will forget you. You have to top up the goodwill; release something new, to remind them.’ I just remember thinking, you know, I couldn’t care less. If they need to be reminded, they never got me in the first place.”

Andrew Stafford

messandnoise.com, Australia’s premier alternative music community and online magazine

August 21 2012

En vérité, je n’ai jamais manqué de chansons

Interview parue sur la Blogothèque (online magazine)

Mercredi 4 novembre, 9h12 à Paris. Dans six jours, Peter Milton Walsh sera de retour sur une scène (j’allais dire une scène française, mais disons, une scène, une scène tout court). Je vous avoue que j’ai encore du mal à y croire, et pourtant il est là, il est à Paris (enfin, normalement, si tout va bien !) Je termine la retranscription de cette interview dans l’avion qui revient de New York (où nous venons de jouer avec 49 Swimming Pools), et Peter, lui, doit être à Paris depuis lundi soir. Plus tard, dans la soirée, quand la Blogothèque publiera ce texte, on sera sans doute occupés à boire un verre. Ou dix. On ne s’est pas vu depuis quatorze ans.

Ces derniers jours, Peter a répondu à quelques questions, par e-mails successifs, alors qu’il était encore à Sydney. En voici la transcription. Drôle d’interview, sinueuse, un peu déroutante, en plusieurs morceaux que j’ai essayé de recoller le moins mal possible (j’utilise aussi un long mail qu’il a envoyé à Olivier Granoux, de Télérama/Sortir ). La pensée de Peter est, vous le verrez, à la fois particulièrement affutée, et d’une profondeur qui filera le frisson à ceux pour qui ses disques sont des trésors intimes. Notre grand ami d’Australie y glisse aussi, au détour d’une question, quelques mots qui expliquent pourquoi nous étions sans nouvelles depuis plus de dix ans, quelques mots d’un drame familial terrible que je ne pensais pas qu’il évoquerait ici. Il le fait avec un courage infini, et avec une pudeur que je demande à ceux qui souhaiteront discuter un moment avec lui la semaine prochaine de respecter absolument.

Chacun pourra désormais comprendre pourquoi ce retour est un pas gigantesque dans la vie de Peter. S’il le fait en France, je pense que c’est parce qu’il a la conviction que nous saurons lui renvoyer un peu de la joie profonde qu’il a nous a donnée avec ses disques depuis le milieu des années 80. Donnons-lui raison, ladies and gentlemen, let’s be good to him, like he’s g(o)od to us. (ET)

Peter, à quoi ressemble ta vie en 2009 ?

A une rue dans un quartier de Sydney, Australie. Une famille, une maison, une cour à l’arrière de la maison, un piano, quelques guitares, un petit studio d’enregistrement. Mes enfants jouent de la flute, de la clarinette et du piano. J’ai eu toutes sortes de boulots, dans tous les genres, dans plein d’endroits différents. Motivation unique : me faire un peu d’argent, ce qui n’a jamais été mon fort dans la vie.

Le dernier boulot que j’ai pris m’a été proposé à un moment où j’avais envie de disparaître, et c’est exactement ce qui s’est passé : ce boulot m’a permis ça, une forme de soustraction. J’ai été, pendant un long moment, comme un homme déguisé, un homme qui décide de s’effacer. Parfois, les gens font ça : ils se trouvent un visage derrière lequel se planquer, un visage qui cache le chaos intérieur. En vérité, je n’ai jamais manqué de chansons. J’ai surtout manqué de cœur.

Tu avais donc bel et bien arrêté la musique ?

Publiquement, oui. Je n’avais plus la force… Les groupes, c’est comme des ancres de bateau. C’est comme votre travail, votre maison, votre famille, ça vous donne un repère. Mais parfois les repères se brouillent… Un groupe, ça peut aussi vous aider à rester debout, à rester d’un bloc. Tu as envie de voyager, de voir le monde ? Alors tu dois suivre les règles du jeu. Tu écris, tu répètes, tu enregistres, tu trouves un deal, puis tu sors ton disque, et c’est parti, ça devient public : single, album, vidéo, tournée. La route est pré-tracée. Lavez, rincez, recommencez. Evidemment, celui qui ne suit pas ces étapes avec application renonce à tout un tas de choses. Mais alors, il perd aussi un droit important : le droit de se plaindre.

LES GROUPES, C’EST COMME DES ANCRES DE BATEAU… ÇA VOUS DONNE UN REPÈRE.

J’ai toujours voulu faire gaffe à un truc : ne pas me laisser griser par le succès. Alors on peut dire que j’ai réussi, oui, j’ai tenu cet objectif assez magnifiquement même ! Un peu d’ambition en plus ne m’aurait sans doute pas fait de mal, mais bâtir une « carrière » me semblait demander une stabilité dont je ne me sentais pas capable. J’ai passé mon temps à bouger, à partir, à partir encore. Pendant très longtemps, j’ai eu du mal à m’accrocher à un sentiment, peu importe sa nature, en me disant qu’il serait encore là, en moi, cinq minutes plus tard. Alors c’est dur de construire quoi que ce soit… Et puis si, quand même, à un moment, il y a eu un peu de stabilité dans ma vie, et dans mes sentiments, alors pendant quatre ou cinq ans, la musique a été comme un travail. Mais ensuite, j’ai dû arrêter, parce que j’avais quelque chose de plus important à faire.

Tu as vécu dans de nombreuses villes, très différentes les unes des autres, Brisbane, New York, Londres, Sydney… Quels sentiments t’inspirent ces souvenirs, et ces différents endroits ?

Le souvenir le plus marquant, c’est cette idée d’être sans cesse en train de bouger, ce sentiment que tout n’était que temporaire, que je n’allais jamais rester très longtemps – de mon fait, le plus souvent. Je ne crois pas que j’étais particulièrement ingérable, même si je sais qu’on m’a un peu prêté cette réputation. Disons que les choses se sont passées ainsi, que je le veuille ou non. J’ai toujours été attiré par toutes sortes d’expériences, et ayant rapidement fait le tour de celles qu’on peut connaître en étant musicien, j’ai voulu en vivre d’autres. Toujours vite, toujours en bougeant d’un coin à l’autre. Le risque, quand on fait ça, c’est qu’on peut manquer certaines marches qu’il faudrait normalement gravir patiemment, de manière à construire une « carrière ». Des marches, j’en ai négligé beaucoup. Et du coup, je me suis souvent retrouvé à la case départ, à me demander : « mais, alors combien de fois vais-je me retrouver à la case départ ? ».